Full Court Press

The forecast for offshore wind has become increasingly uncertain.

Written by Brian Bushard

Photography by Kit Noble

The 200 wind turbines off the coast of Cape May, New Jersey, were supposed to tower over the water, generating enough electricity to power more than 700,000 homes. But that project has been stopped in its tracks, and possibly for good. It was a pair of blows in a matter of months that stopped it. The first blow: Oil giant Shell pulled out of the project, erasing a$1 billion investment it had in the wind farm. Then in March, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) pulled federal permits for Atlantic Shores, the two-part project off the coast of New Jersey, even though the project had already received federal approval.

The EPA’s decision marks the culmination of a months-long effort by local opposition groups and elected officials to stop the project. It also comes as offshore wind, a hallmark of the Biden administration, faces new uncertainties in a second Trump term, casting more than two dozen offshore wind projects along the Eastern Seaboard into doubt. Those blows to the Atlantic Shores project have now become a source of inspiration for ACK for Whales, a Nantucket group that’s trying to keep offshore wind farms from being constructed in the waters south of Nantucket—and they’re asking the town to join them.

“[Energy companies] know that public opposition is the number one thing that kills these projects, and when they see a concerted effort with businesses, municipalities and environmental groups all banding together and saying we don’t want this here, they say, ‘Holy crap, this is going to take a long time, we are going to be fighting a long slog of a fight,’” said Amy DiSibio, a board member of ACK for Whales.

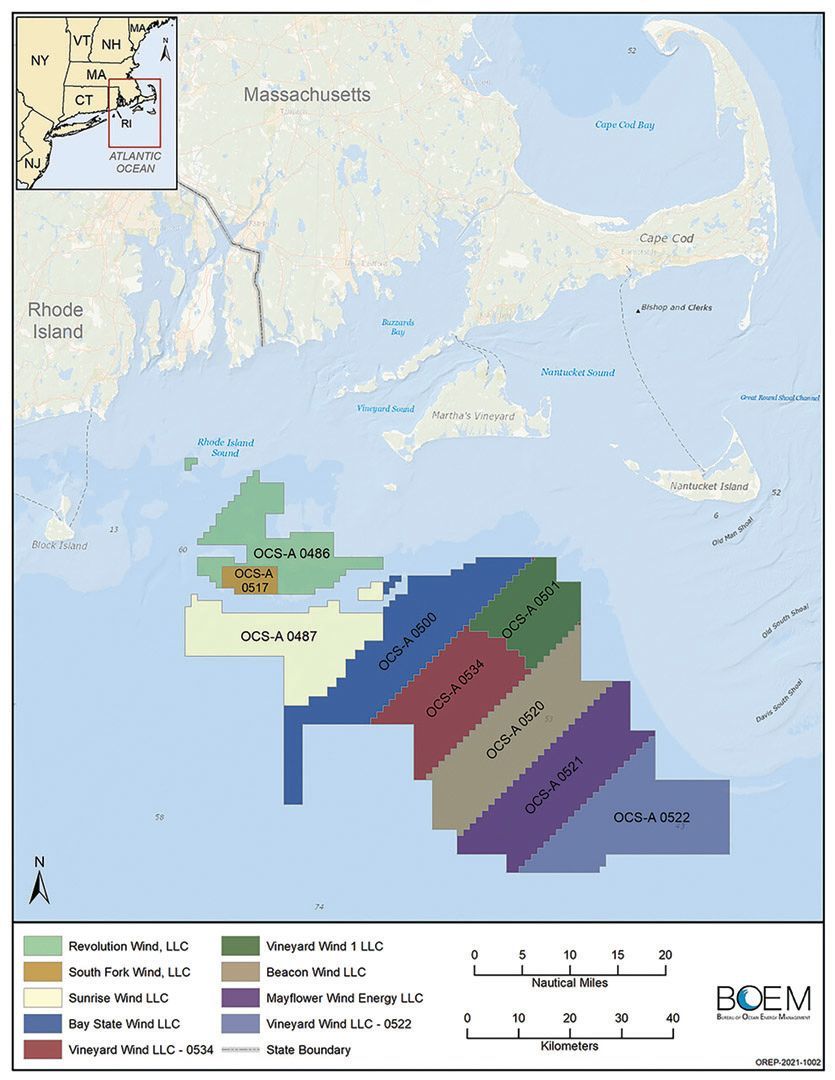

While the focus for Nantucket has by and large been on Vineyard Wind’s 62-turbine project 15 miles south of the island, that wind farm is only one of a handful with a lease off Nantucket’s shores, a 60-plus-milearray that stretches west to the waters south of Newport, Rhode Island. Since those proposed sites lie in federal waters, Nantucket officials have maintained they have not had a say in the permitting process, save for a2019 vote of the Conservation Commission approving a Vineyard Wind cable connecting the turbines to the mainland through Muskeget Channel.

At the time, Select Board members were advised by town counsel to support the project, structuring a deal—a good neighbor agreement—with Vineyard Wind to mitigate its visual effects. Vineyard Wind agreed to paint its turbines off-white and install a type of nighttime lighting that would only go off when planes were overhead (Vineyard Wind only began testing its aircraft detection lighting system in February). The town—as well as cosigners the Maria Mitchell Association and Nantucket Preservation Trust—secured$16 million through that deal in exchange for support of the project. Five years later, and in the wake of the project coming under fire last summer because of a collapsed blade that left fiberglass and styrofoam particles scattered across Nantucket’s south shore, a group of residents and some town officials are now wrestling with the idea of exiting the good neighbor agreement.

"If that whole lease area gets built out, what Nantucket needs is a huge seat at the table,” ACK for Whales board member Veronica Bonnet said. “Just because you’re a proponent of offshore wind doesn’t mean you should be putting your head in the sand about the impacts of it. All energy has an impact. This isn’t a little fairytale where we get to build windmills off Nantucket and everything is great. This is a massive amount of power in the hopes of supplying electricity to millions of homes in New England. If that’s what you’re a proponent of, then you ought to be a proponent of getting out of the good neighbor agreement and into an agreement that protects Nantucket from a massive power plant.”

Dawn Hill Holdgate, one of two Select Board members who were on the board in 2020 when the agreement was signed, believes Vineyard Wind already broke the terms of the agreement when it waited three days to inform town officials about the broken blade last summer. She felt the same way after a two-day delay in communication to the town after a lightning strike on the same turbine over the winter. At a heated Select Board meeting in February, she argued the community had been misled about the visual and environmental impacts of the project when it was proposed. Vineyard Wind did not return N Magazine’s request for comment.

“What I think we have come to realize is that the impacts outweigh any financials,” Hill Holdgate said. “It really doesn’t matter what the dollar figure is. It was very misleading what we were told in2020. The impacts are far greater visually, and now we know the environmental impacts are more significant."

Just days into his second term in office, President Donald Trump released an executive order slamming the brakes on offshore wind, halting new federal leases and setting the stage to potentially amend or terminate existing offshore wind leases like Vineyard Wind or SouthCoast Wind off Nantucket, pending a federal review by the Department of the Interior. SouthCoast’s plan calls for 141 turbines standing over1,000 feet tall, taller than Vineyard Wind’s 850-foot turbines.

“My preference would be for the entire project to stop. I am hopeful these other projects will be stopped or delayed with the new administration,” Hill Holdgate said. The town in March appealed the federal approval of SouthCoast Wind, citing an alleged failure to protect the island’s status as a national historic landmark and a failure to “take a hard look at environmental impacts.”

But a federal delay in the rollout of offshore wind has some state and federal officials on edge. “There’s a need for offshore wind,” Rep. Bill Keating, a Democratic Congressman representing Nantucket, said.

That need stems from a state comprehensive energy plan developed during Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration, when Plymouth’s Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station was decommissioned, leaving Massachusetts reliant on imported natural gas. The state has explored hydropower through a transmission project from Canada to Maine, though the recent federal trade war with Canada has Keating worried that option would see state ratepayers paying a fortune for energy. Purchasing natural gas is another option, though Keating said that too would be “enormously expensive and volatile.”

“What was initially a project in offshore wind that focused on the needfor alternative and renewable energy became part of our plan to get the power that we need,” Keating said. “We’re in a very precarious spot where we live. We’re at the end of the line in terms of energy sources.”

Democratic State Sen. Julian Cyr, who represents Nantucket on Beacon Hill, agreed with Keating. The conversation around wind energy, he argued, should start with electricity costs, which he said have become “astronomical on Cape and Islands” because of the state’s reliance on natural gas. As of January 2025, Massachusetts consumers pay the fourth highest price for electricity in the country (30.08 cents per kilowatt hour), only behind Rhode Island, California and Hawaii, according to data from the Energy Information Administration.

Cyr has been consistent in his criticism of Vineyard Wind’s communication following the blade failure—which led to a federal suspension on the project and which GE Vernova attributed to a “manufacturing deviation” at a Canadian factory where the blades were made. But Cyr also argued the blade failure should not be cause to walkaway from offshore wind altogether.

“Offshore wind is a critical source for the electric grid for Massachusetts and New England,” Cyr said. “We’re an importer of our energy and that’s a part of why our energy costs are so high, and that burden falls to our residents."

According to Vineyard Wind, the 800-megawatt offshore project has the capacity to generate energy for more than 400,000 homes and businesses in the state, reducing carbon emissions by an estimated1.6 million tons per year. Offshore wind proponents have long touted the alternative energy source’s ability to reduce Americans’ carbon footprint, a major policy goal of the Biden administration. That goal: 30gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030, or enough to power 5.25 million homes.

What offshore wind proponents and some opponents seem to agree on is the importance of transitioning away from traditional greenhouse gases. Congressman Jeff Van Drew, a Republican from New Jersey and one of the most outspoken critics of offshore wind on Capitol Hill, even said he was in favor of renewable energy, though his preference is for solar—as well as nuclear—energy.

“This has been a great opportunity to monetize the global push for the panacea for climate change,” DiSibio said. “It’s politically popular to talk about it, but in the end, people really aren’t focusing on the impacts, and the trade-off just isn’t there.”

But without offshore wind, some officials worry Americans’ reliance on fossil fuels will only accelerate, exacerbating both pollution and the negative impacts of climate change such as sea-level rise.

“Islanders have seen and are not happy about the adverse consequences of a single blade failure,” Cyr said. “The prospect of drilling off our shores for natural gas could truly present catastrophic consequences for our shores, let alone only furthering the climate crisis.”

Several offshore wind projects down the Eastern Seaboard have begun construction. In addition to Vineyard Wind’s 62 turbines, other projects include the 12-turbine South Fork Wind Farm south of Rhode Island, the Block Island Wind Farm and Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind, a pilot project consisting of two turbines with plans for 174 more. In total, 36offshore wind projects have secured federal leases off the East Coast from Maine to South Carolina.

Just south of Vineyard Windis another proposed project called New England Wind, a planned129-turbine wind farm 24 miles southwest of Nantucket. ACK for Whales is challenging that project as well, asking the Select Board to sign on as a co-plaintiff. In March, the group petitioned the EPA to review its Clean Air Act permits for New England Wind, the same permits that were pulled for Atlantic Shores off the coast of New Jersey. It’s not the group’s first legal challenge.

ACK for Whales had also sued to stop the Vineyard Wind project, taking its case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, though the nation’s highest court declined to hear the case. In March, the group launched a new challenge against Vineyard Wind through the EPA, seeking to revoke its Clean Air Act permit.

“The missing link is we want the Select Board,” DiSibio said. “If the town and county of Nantucket push back on this, then everything is a lot stronger.”

Matt Fee, who serves as the Select Board’s vice chair, said the board is considering all of its options when it comes to the good neighbor agreement. The Maria Mitchell Association exited the agreement last fall. At the same time, over 150 businesses have signed a petition urging the Select Board to withdraw from the deal. es that agreement, the Select Board has also asked islanders to lobby state and federal preservation authorities over mitigation for SouthCoast Wind, and has publicly objected to a proposed mitigation plan from SouthCoast that would have seen the town receive $150,000in mitigation funding—a drop in the bucket of the good neighbor agreement’s $16million, and a number Hill Holdgate called a joke.

“We have greater leverage now because [Vineyard Wind] is in breach of the agreement in my mind,” Hill Holdgate said. “We have seen further unintended consequences with the blade failure, the debris, the impact on summer tourism and local businesses, and now leaving it the way they have since last summer, it’s been allowed to be hit by lightning causing further issues. We are in a position to do a lot more about it now, but it’s still an uphill battle."