ELECTRIC AVENUE

Is this the ferry of the future?

story by Jason Graziadei and Eliza Bowman

Earlier this summer, Sweden made a splash when it announced that electric ferries in Stockholm would soon be commuting passengers to and from the nearby island of Ekerö. Cruising at up to thirty-five miles per hour, the battery-powered Candela P-12 represents the new frontier of green energy gradually sweeping across maritime communities in Europe. Here in the United States, with fuel prices surging and with Cape Air recently introducing a fleet of electric aircraft, one might wonder when electric ferries will be docking on Nantucket.

The Steamship Authority is exploring the feasibility of operating electric ferries, but the possibility of implementing such technology on the Nantucket route—at least at this point—seems to be a distant dream. All-electric ferries would require significant capital investment both for new vessels and the infrastructure to support them, and would be far more feasible on the Steamship’s Martha’s Vineyard route than on the Nantucket route due to the greater distance involved.

Those are among the conclusions of the Hybrid Propulsion Study commissioned by the Steamship Authority and recently presented by its consultant, the Elliott Bay Design Group, a naval architecture and marine engineering firm. “We keep coming back to energy,” said John Waterhouse, the founder and chair of Elliott Bay Design Group, regarding the challenges of going all-electric on the Nantucket route. “The Vineyard route uses significantly less energy than Nantucket because it’s shorter. The drawbacks of Nantucket are, first of all, can you get rapid charging on both ends of the route? Our feeling is that’s not possible on the Nantucket route and at this current time.”

The Steamship Authority’s fleet of ten ferries and freight boats currently runs on diesel fuel, and together they consume roughly three million gallons in an average year on the Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard routes. As some coastal communities on the West Coast and elsewhere begin to adopt hybrid and electric propulsion systems for their ferries to reduce emissions, the Steamship Authority’s study was undertaken to explore a handful of options and provide cost estimates.

Those options included diesel hybrid systems and an all-electric option, but as the study noted, “the Hyannis to Nantucket route is not being considered for all-electric propulsion at this time.”

The Elliott Bay Design Group estimated that both the capital and operating costs of all-electric propulsion were the highest of the options it explored, including the baseline of a diesel mechanical system. The study looked at an equivalent of the Steamship Authority’s M/V Woods Hole ferry to examine the alternative propulsion configurations—a vessel that would be a 235-foot passenger ferry intended for service on both the Nantucket and Vineyard routes.

To go all-electric on the Vineyard route with a boat of that size would require at least $12.2 million in capital costs and $17.7 million in operating costs over a ten-year period. There was no corresponding cost estimate for Nantucket to go all-electric. Another factor Waterhouse touched on was the source of electricity that the ferries would need to draw from through their “shore power” charging stations. In Washington State, where ferry operators are in the process of implementing all-electric vessels (albeit on shorter routes), they are drawing electricity from hydroelectric sources. That wouldn’t be the case in Massachusetts.

“If your electricity is coming from burning coal, and that electricity is powering your ferry, how green is that?” Waterhouse said.

While electric ferries might not be landing on Nantucket in the near future, the harbor might soon be dotted with fleets of e-powered watercrafts. Electric boats are growing in popularity as technological innovations move at lightning speed alongside growing environmental consciousness. Personal chargeable watercrafts are being developed all around the world with the goal to revolutionize the boating industry. The Swedish marine technology company Candela—which is responsible for the P-12 ferry slated to serve Stockholm—introduced its new C-8 leisure boat this spring, a model that glides on top of the water’s surface with hydrofoils. These fins reduce energy output as well as virtually eliminating wake behind the boat.

Hydrofoils are a key component of the rise in electric watercrafts because of how they provide speed and energy efficiency by keeping the body of the boat above water. In Maine, the Lyman-Morse shipyard is currently overseeing the building of the Navier 27, an electric dayboat that will also employ retractable hydrofoils. Set to launch this fall, the Navier 27 is designed to achieve sustainability while prioritizing high range on its charge as well as energy efficiency without compromising on speed. It will reach a top speed of thirty knots and have a seventy-mile range at twenty knots.

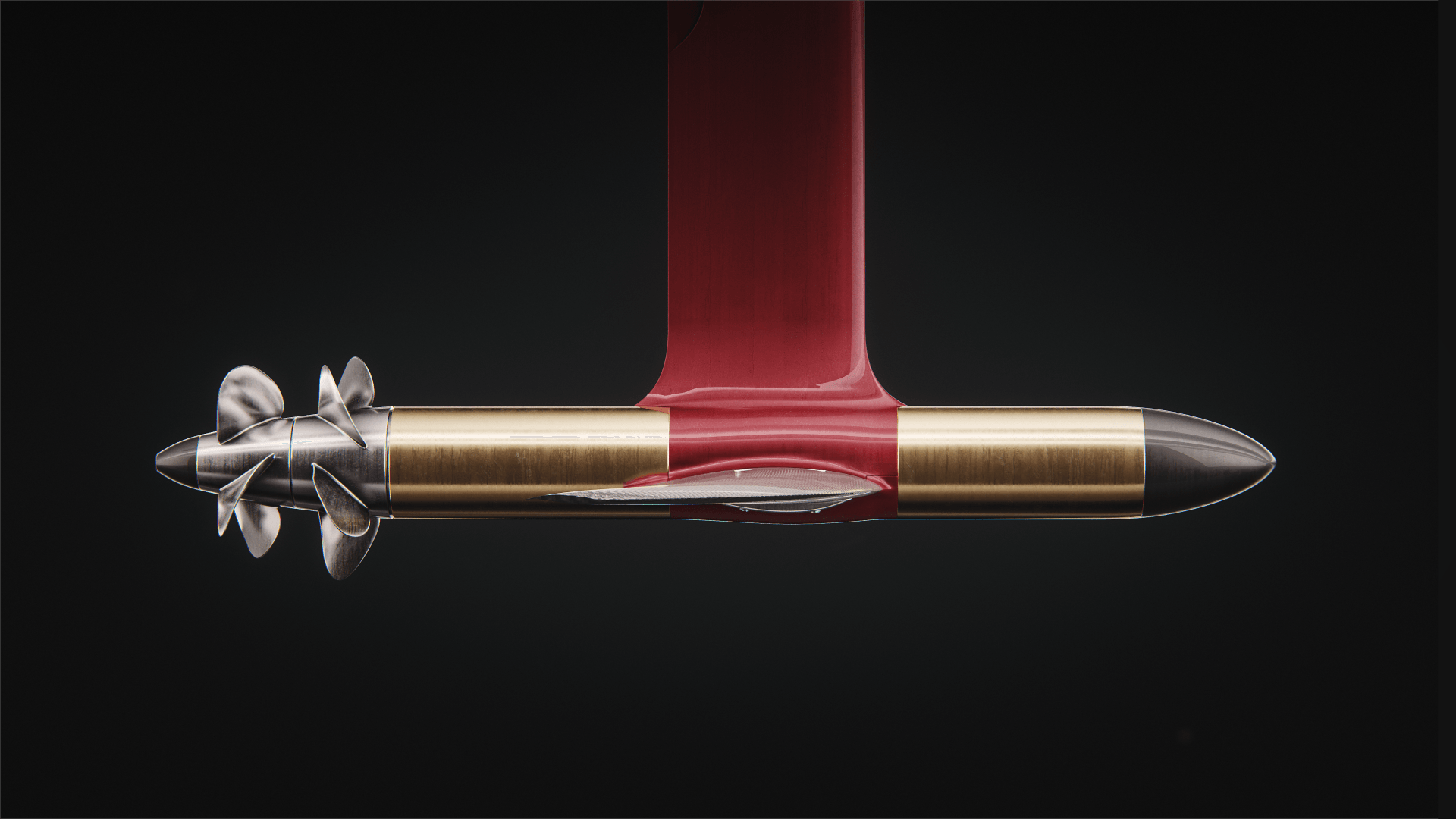

Pure Watercraft is another company embracing a turn toward electric boating with its various models of electric pontoon boats, bass boats and launches powered by a battery-charged electric motor. The goal of these innovations is to achieve greater energy efficiency by reducing the amount of fuel needed to power such vehicles, as well as minimizing disruption and noise in the surrounding water. Although personal electric watercrafts come with their obstacles, like access to charging stations and actual time to charge, they are an appealing alternative to conventional engines powered by diesel or gasoline by offering an avenue that is more efficient, sustainable and environmentally friendly.