HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF

Nathaniel Philbrick explores how partisanship is sewed into the fabric of the country.

story by Nantucket Magazine

Partisanship is nothing new. Back in 1789, even before he was inaugurated president, George Washington knew he was about to become the leader of an already divided nation. He needed to do something to bridge the differences between those who embraced the Constitution (known as Federalists) and those who distrusted the strong central government the Constitution had created (Anti-Federalists). So he hit the road, traveling by carriage as far north as Kittery Point, Maine, and as far south as Savannah, Georgia.

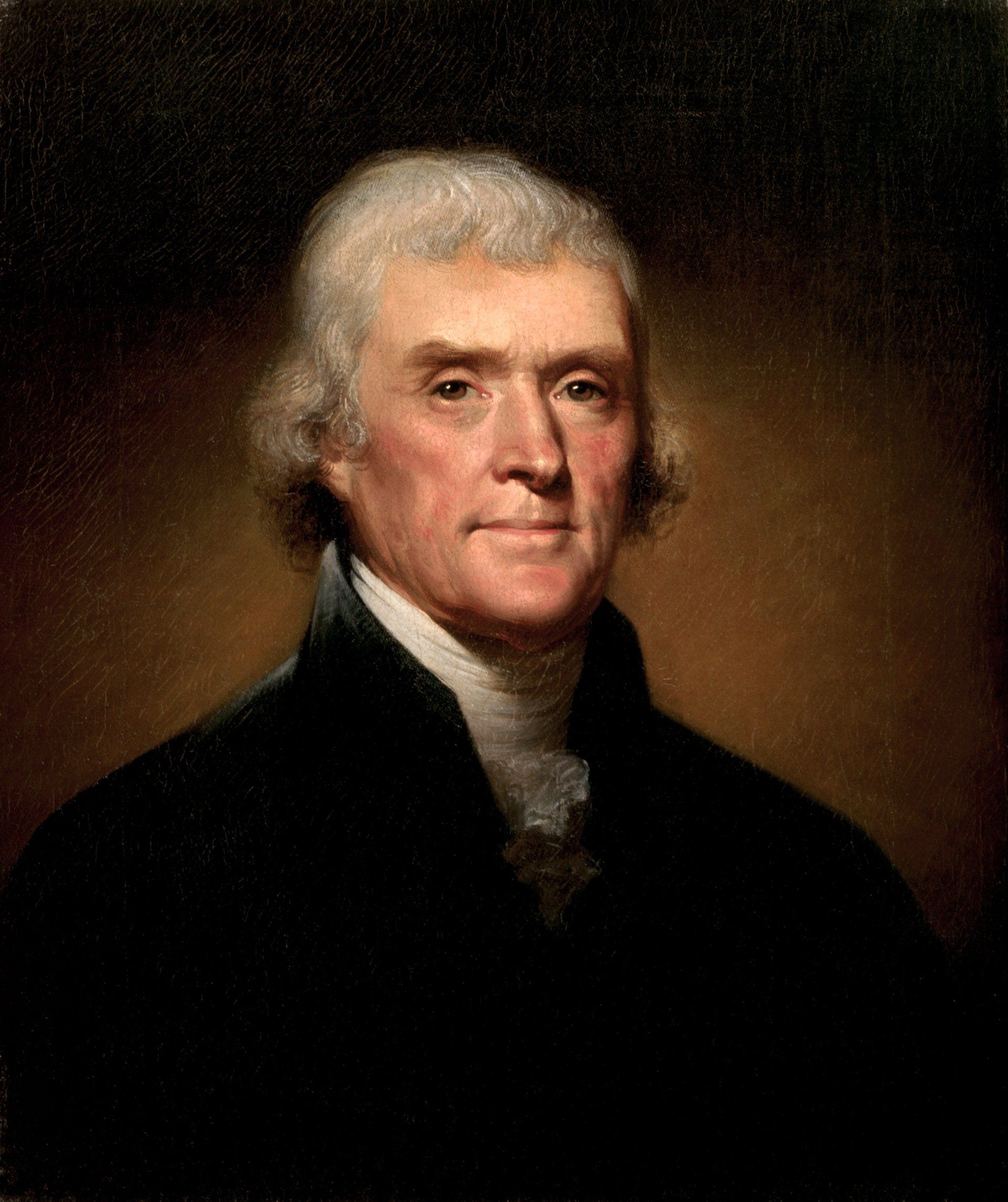

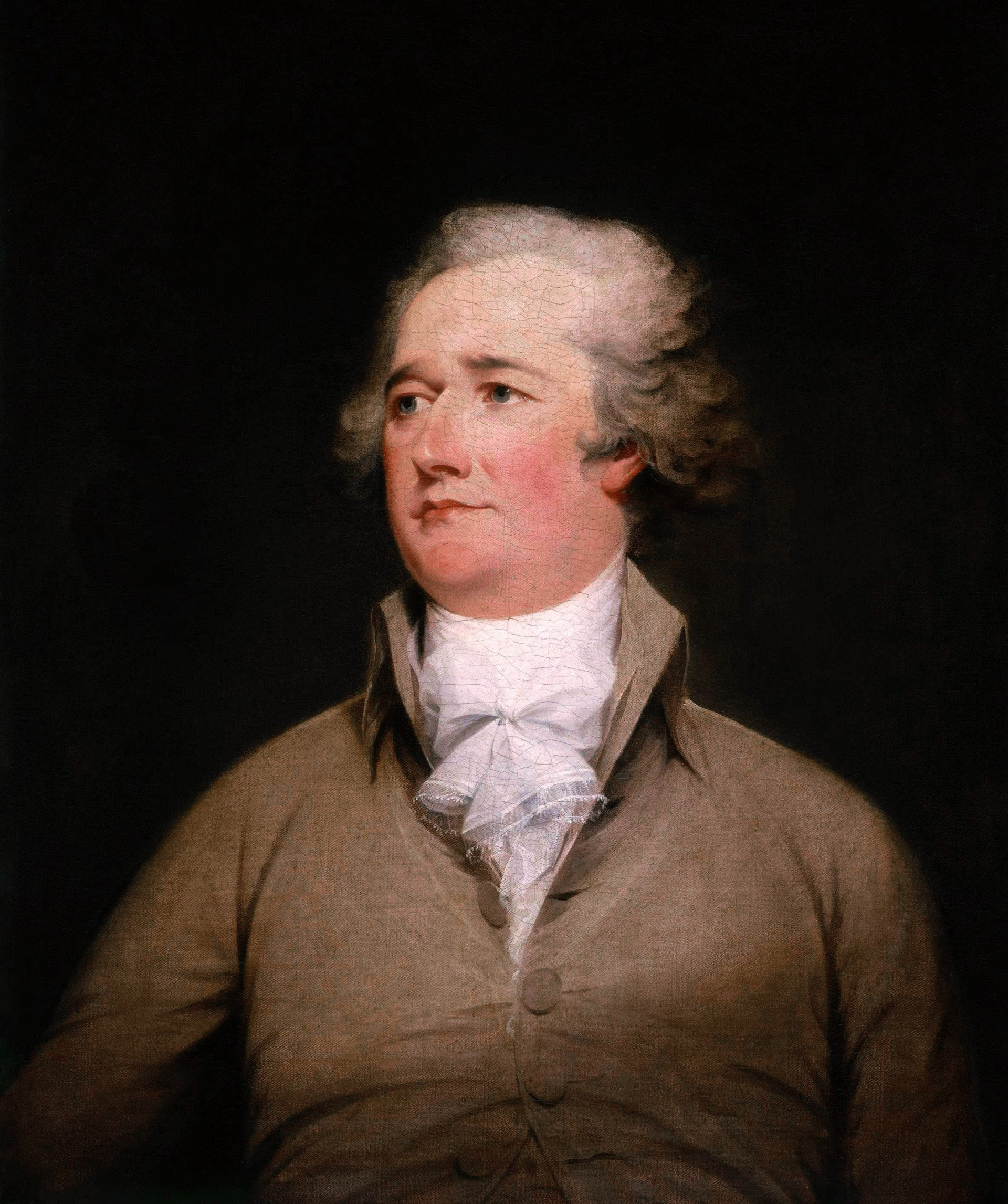

In 2018, as America’s political divide seemed to be widening by the day, award-winning author Nathaniel Philbrick set out to retrace Washington’s travels. Philbrick hoped to put our own fractious times in an instructive historical perspective. Washington succeeded brilliantly in forging a government that was built to last, but he was less successful in bridging the political divide. What follows is an excerpt from the epilogue of Travels with George that describes Washington’s attempts to find some common ground within his own cabinet between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton.

Standing on Mount Mansfield at the end of summer, I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness. Our travels with George had come to an end just as the story of the new nation was beginning. Jefferson and Madison would return to Philadelphia and continue to organize the political resistance, confident they were battling the pernicious forces of monarchy and corruption. In the meantime, Hamilton and the Federalists, equally confident in their righteousness, pushed forward the financial programs on which today’s economy—with all its excesses and inequalities—is built. In the middle was Washington, a Federalist for sure, but a Federalist who recognized there was another point of view.

What bothered him were not the philosophical differences between his two warring cabinet members but their unwillingness to work cooperatively. “Differences in political opinions are as unavoidable as, to a certain point, they may perhaps be necessary,” he wrote to Hamilton. “When matters get to such lengths, the natural inference is that both sides have strained the cords beyond their bearing—and that a middle course would be found the best, until experience shall have pointed out the right mode—or, which is not to be expected, because it is denied to mortals, there shall be some infallible rule by which we could fore judge events.” What both Hamilton and Jefferson needed, Washington seemed to be saying, was a little more humility and self-doubt. Because no one—not even the two most brilliant men of their age—had all the answers.

Unlike Hamilton and Jefferson, Washington didn’t need to be right all the time. He just wanted to make things work. He understood that feasible change is not attained by righteous indignation; it’s understanding that the road ahead is full of compromises if life is actually going to get better. Not Jefferson. When it came to his beloved French Revolution, he insisted that “rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than it is now.” This kind of philosophical dogmatism and melodrama was anathema to Washington. He had spent eight years of his life doing his best to prevent the United States from succumbing to the divisions and violence that were about to consume France. He understood the darkness of self-interest lurking beneath the most high-minded ideals. And yet, despite his inherent skepticism concerning the human condition, he had an abiding faith in the American people. “Although we may be a little wrong now and then,” Washington wrote to his former aide-de-camp Jonathan Trumbull Jr., “we shall return to the right path with more avidity.” Thomas Jefferson had written the Declaration of Independence, but it had been left to George Washington to translate its words into something real—into something that might one day evolve into what the preamble to the Constitution calls “a more perfect Union.”

By subsuming sectional and philosophical interests to the good of the whole, the Union is the antidote to arrogance and self-importance, because there will always be something bigger than a single person, town, city, state, or region—or any single race, religion, sexual orientation, or set of beliefs. The founders never claimed to have created the ideal political system. But no one over the course of the last 244 years has come up with a better form of government. The fact that we are in a position today to find fault with the past is a tribute to what was created by the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the labors of George Washington. If our country is ever going to improve in the future, we need to look the past full in the face today, and there, at the very beginning, is our first president: a slaveholder, a land baron, a general, and a politician, who believed with all his soul in the Union.

From TRAVELS WITH GEORGE by Nathaniel Philbrick, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Nathaniel Philbrick